Erasing Rudyard Kipling

The dangerous impulse to paper over our troubling past and silence our enemies is one we must resist.

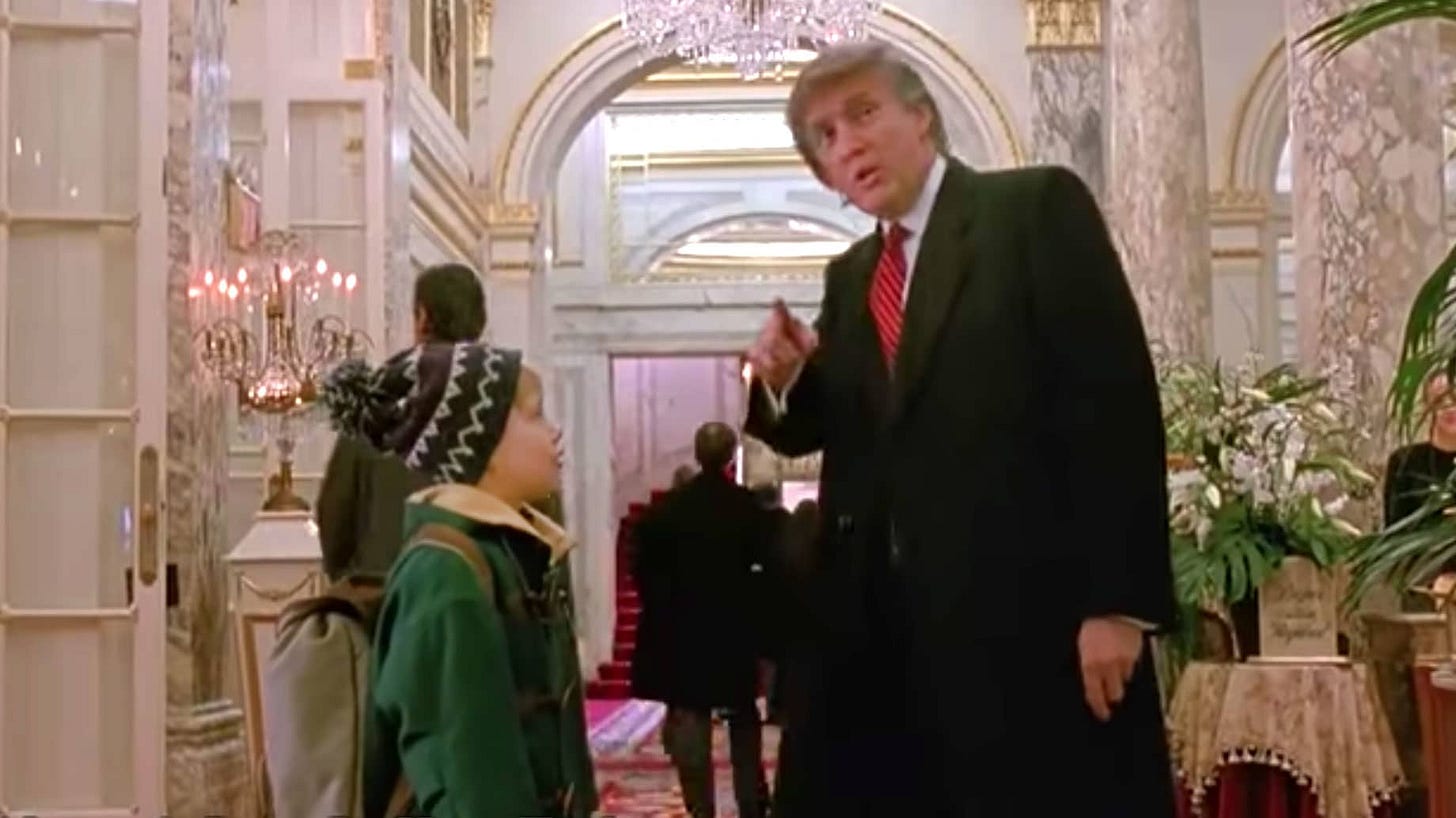

It was a bit jarring, I admit, when I re-watched Home Alone 2 for the first time in many years and came across this scene:

I am about ten months younger than Macaulay Culkin—who is now 40 years old—so I hadn’t heard of Donald Trump when I first saw the film. I had just turned 11 when it came to theaters. Culkin had just turned 12. Watching Home Alone and Home Alone 2 when they came out, I could very much imagine myself in these situations. A young boy’s imagination can easily include fending off Wet Bandits with cleverness and booby traps. I’d seen The Goonies already. Anything was possible.

When I first saw Home Alone 2 and Kevin, now lost in New York City, found his way to the Plaza Hotel and bumped into an older man who vaguely pointed him in the right direction, I didn’t think twice about the scene. I promptly forgot about it afterward—what reason would a boy have to recall a 7-second cameo from some old dude in a suit?

Years later when I saw the film again, I was old enough to know who Donald Trump was. I had moved past the phase where I only knew the word “trump” as a playing card term (we were big on card games in my family) and knew that he was a celebrity businessman who made some reality TV shows that I never watched and was routinely the butt of jokes and an egomaniac. By the time I ever really paid attention to the man, he had started flirting with politics but was far more moderate—advocating, for instance, universal healthcare. “I’m a conservative on most issues but a liberal on health,” he once said. “We must take care of our own. We must have universal healthcare.”

It wasn’t until the Obama years that Trump’s really erratic, conspiracy-minded behavior started. And I won’t really get into that too much. This column is less about questions of left vs right and more about the ethics of censorship and historical preservation, issues that ought to transcend our day-to-day political squabbles.

Still, when I watched Home Alone 2 with my own children several years ago, after Trump had been elected to office and had very much abandoned any attempt at bipartisanship, it was quite jarring to come across this scene again, a scene I had forgotten about once again. This time, there was a lot more to Trump than reality TV star—he was the President of the United States of America, and an enormously divisive figure. What an odd cameo in the middle of an otherwise completely agreeable film.

It turns out, Trump had ‘bullied’ his way into the film. He owned the Plaza and when director Christopher Columbus wanted to film there, Trump said sure, as long as he was given a role.

"Trump said OK. We paid the fee, but he also said, 'The only way you can use the Plaza is if I'm in the movie,'" Columbus told Insider. "So we agreed to put him in the movie, and when we screened it for the first time the oddest thing happened: People cheered when Trump showed up on-screen. So I said to my editor, 'Leave him in the movie. It's a moment for the audience.' But he did bully his way into the movie."

Now, fans are petitioning to have Trump cut from the movie. Some want him digitally replaced with grown-up Culkin; others with Joe Biden. Some just want the scene to be cut entirely. Culkin agrees.

It’s easy to get caught up in the hullaballoo. Trump has diehard fans and detractors. For those who believe his time in the White House was filled with corruption, bigotry and other sins, it’s a natural—if misguided—impulse to want to scrub his Hollywood history and replace it with something less offensive.

But it’s one thing to reverse Trump’s politic legacy and another thing entirely to attempt to erase him from the history books, or sweep his rise in pop culture under the rug. The rise of Trump was not merely in the realm of the political; he was, for better or worse, the first reality TV celebrity to take the Oval Office. His trajectory aired on NBC first; Fox News came later. You can’t erase him from the pop culture he inhabited without jeopardizing our understanding of his place in American politics and what that means. Besides, we’re all pop culture, whether we’re making it or consuming it or critiquing it. We can’t be free of our own past so easily, so guilt-free.

And while I shed no tears that Trump was banned from Twitter—allow me the occasional schadenfreude—the fact that Twitter has become such an important form of communication for both our private and public spheres is something that should give everyone pause. The First Amendment only covers government censorship, but we shouldn’t pretend that ethical concerns around freedom of speech in a high-tech, social media-driven future aren’t something we’ll eventually have to contend with.

Giant corporate entities with powerful incentives to manipulate information, massive reach into all segments of society, and dubious oversight could pose their own kind of existential threat to democracy and liberty. This applies as much to Twitter as it does to older forms of media: talk radio, cable news and so forth.

How you actually balance the equation—between private companies, free speech, limited government and the spread of dangerous propaganda and untruths—is a question we’ll be debating for a long time to come. On Twitter and Facebook and in the halls of government and corporate board rooms, on talk radio and TikTok.

In the meantime, we should be careful what we scrub from the records. The racism we encounter in older film and animation can be hard to watch, but it gives us a glimpse into our past, and the views and attitudes that shaped our forebears. Even relatively mild sitcoms of the past, like I Love Lucy, include social norms and gender roles that most of us find antiquated now. Maybe even offensive. Should we cancel Lucy?

I’m less concerned with tearing down statues than I am with tearing out history pages.

We can avoid paying homage to long-dead racists or Confederate generals while still studying their lives, many of whom were not merely good or bad; many of whom were simply products of their time.

We can rename streets and buildings that currently bear the names of long-dead bigots without sanitizing the curriculum.

We can acknowledge the troubling nature of so many artists and writers and scientists and clergy while still believing that the study of these people and their work won’t always take place in safe spaces.

There is a place for transgressive art and comedy and literature that, by definition, may offend or cause distress; a place for a critique of tradition and a critique of progress; and a case to make for both progress and tradition as dual—or perhaps dueling—guide posts. It’s messy business, civilization, but someone has to do it.

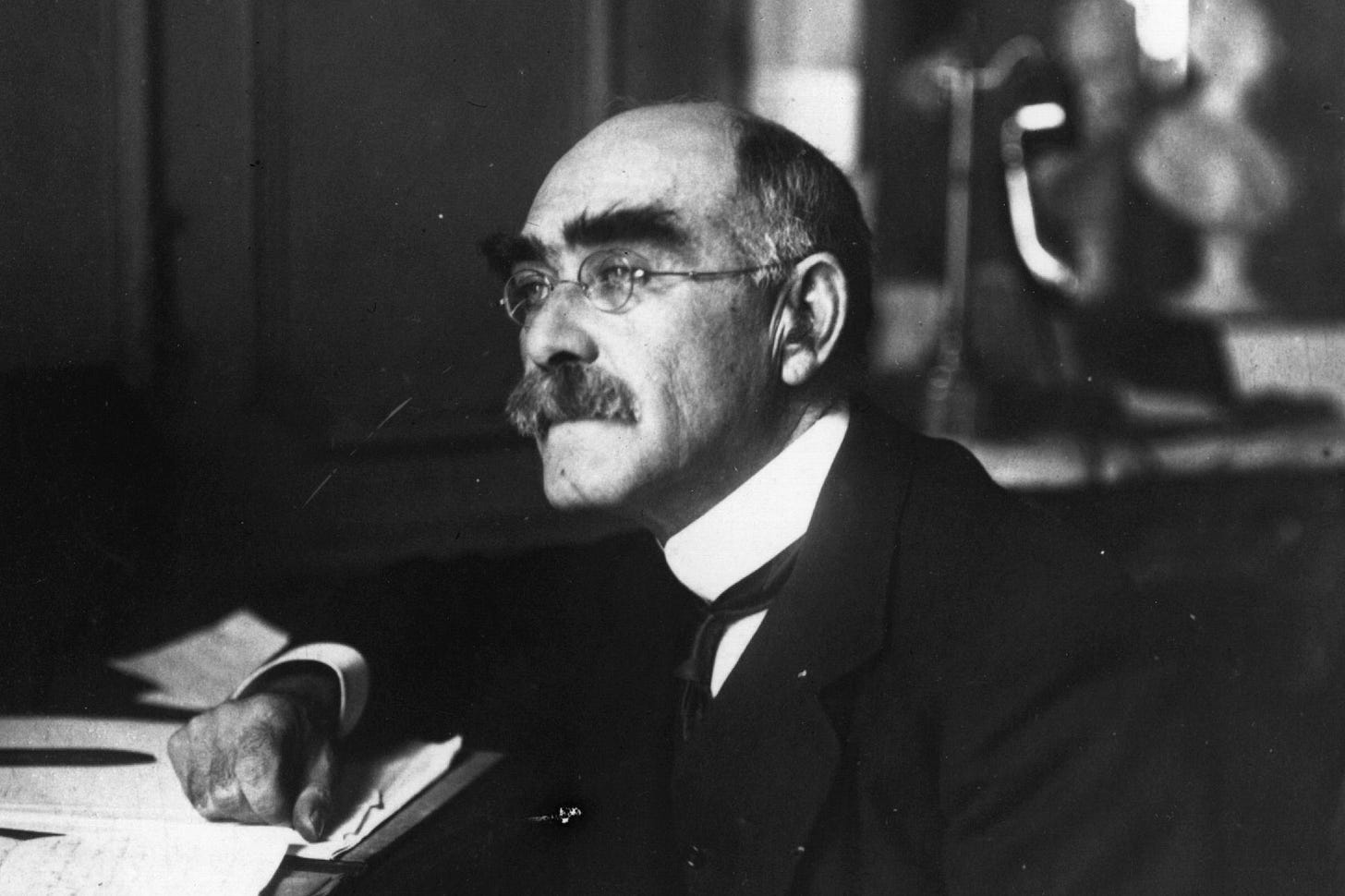

Erasing Rudyard Kipling

I read a news story a few years ago about Manchester University students painting over a mural of the poem “If” by Rudyard Kipling, who they called a racist and an imperialist. They replaced it with Maya Angelou’s poem “Still I Rise.”

The students at the time said that this was “a statement on the reclamation of history by those who have been oppressed by the likes of Kipling for so many centuries, and continue to be to this day” but I wonder if that’s really true. Covering up older poems from different eras with newer ones doesn’t do much of anything really.

Vanishing “If” could, on the other hand, dim our awareness of who Kipling was and his stories and the imperialist history of Great Britain in India that he chronicled and, yes, advocated for as well. Perhaps students at Manchester would be better served thinking about their own country’s colonialist mishaps in Asia than by a poem from an American poet whose work is largely about the struggle of black people in the New World.

And perhaps both poems have something to offer. Perhaps both poems are more alike than they are different, and maybe that matters. “Still I Rise” is about self-confidence and rising above adversity; “If” is a poem about striving to be the best you can be, in the face of whatever obstacle.

Angelou’s includes lines like:

“You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.”

And Kipling’s:

“If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same”

Kipling’s poems are not only for white people any more than Angelou’s are for black people. Poetry is for everyone. So is film and art and literature. Donald Trump in the lobby of the Plaza Hotel awkwardly motioning Kevin in the right direction is for everyone. We shouldn’t forget even a little of our history lest we become doomed to repeat it.

“Of course he was a racist,” said Janet Montefiore, a professor emeritus at the University of Kent and editor of the Kipling Journal, when “If” was painted over. “Of course he was an imperialist, but that’s not all he was and it seems to me a pity to say so.” He was also “a magical storyteller” and his perspective a piece of history.

“You don’t want to pretend that it all didn’t happen,” she said.

And that, dear readers, is exactly the point.

Read “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou here.

Read “If” by Rudyard Kipling here.

Read them both. This is the way.

Why on earth would anyone erase "If"? There's nothing remotely racist or colonialist about it. It's a poem of fatherly advice. What's most pitiful is how much today's most ardent progressives resemble China's Red Guards.

Scrubbing things from history is a dangerous precedent and isn't really accomplishing anything. Watching I Love Lucy isn't going to turn me into a misogynist and watching Dukes of Hazzard, Tom and Jerry, or Gone With the Wind isn't going to turn me into a racist. Do these people want to live in an alternate reality? Once you erase parts of history, it's not real and you don't have the full context to learn from it. Should we ban Benjamin Franklin's autobiography because of the comments about blacks and Native Americans? Will any of this solve the problems that minorities face in this country?